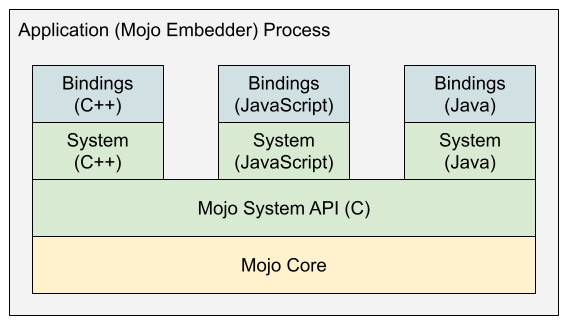

1 # Mojo 2 3 [TOC] 4 5 ## Getting Started With Mojo 6 7 To get started using Mojo in applications which already support it (such as 8 Chrome), the fastest path forward will be to look at the bindings documentation 9 for your language of choice ([**C++**](#C_Bindings), 10 [**JavaScript**](#JavaScript-Bindings), or [**Java**](#Java-Bindings)) as well 11 as the documentation for the 12 [**Mojom IDL and bindings generator**](/mojo/public/tools/bindings/README.md). 13 14 If you're looking for information on creating and/or connecting to services, see 15 the top-level [Services documentation](/services/README.md). 16 17 For specific details regarding the conversion of old things to new things, check 18 out [Converting Legacy Chrome IPC To Mojo](/ipc/README.md). 19 20 ## System Overview 21 22 Mojo is a collection of runtime libraries providing a platform-agnostic 23 abstraction of common IPC primitives, a message IDL format, and a bindings 24 library with code generation for multiple target languages to facilitate 25 convenient message passing across arbitrary inter- and intra-process boundaries. 26 27 The documentation here is segmented according to the different libraries 28 comprising Mojo. The basic hierarchy of features is as follows: 29 30  31 32 ## Mojo Core 33 In order to use any of the more interesting high-level support libraries like 34 the System APIs or Bindings APIs, a process must first initialize Mojo Core. 35 This is a one-time initialization which remains active for the remainder of the 36 process's lifetime. There are two ways to initialize Mojo Core: via the Embedder 37 API, or through a dynamically linked library. 38 39 ### Embedding 40 Many processes to be interconnected via Mojo are **embedders**, meaning that 41 they statically link against the `//mojo/core/embedder` target and initialize 42 Mojo support within each process by calling `mojo::core::Init()`. See 43 [**Mojo Core Embedder API**](/mojo/core/embedder/README.md) for more details. 44 45 This is a reasonable option when you can guarantee that all interconnected 46 process binaries are linking against precisely the same revision of Mojo Core. 47 To support other scenarios, use dynamic linking. 48 49 ## Dynamic Linking 50 On some platforms, it's also possible for applications to rely on a 51 dynamically-linked Mojo Core library (`libmojo_core.so` or `mojo_core.dll`) 52 instead of statically linking against Mojo Core. 53 54 In order to take advantage of this mechanism, the corresponding library must be 55 present in either: 56 57 - The working directory of the application 58 - A directory named by the `MOJO_CORE_LIBRARY_PATH` environment variable 59 - A directory named explicitly by the application at runtime 60 61 Instead of calling `mojo::core::Init()` as embedders do, an application using 62 dynamic Mojo Core instead calls `MojoInitialize()` from the C System API. This 63 call will attempt to locate (see above) and load a Mojo Core library to support 64 subsequent Mojo API usage within the process. 65 66 Note that the Mojo Core shared library presents a stable, forward-compatible C 67 ABI which can support all current and future versions of the higher-level, 68 public (and not binary-stable) System and Bindings APIs. 69 70 ## C System API 71 Once Mojo is initialized within a process, the public 72 [**C System API**](/mojo/public/c/system/README.md) is usable on any thread for 73 the remainder of the process's lifetime. This is a lightweight API with a 74 relatively small, stable, forward-compatible ABI, comprising the total public 75 API surface of the Mojo Core library. 76 77 This API is rarely used directly, but it is the foundation upon which all 78 higher-level Mojo APIs are built. It exposes the fundamental capabilities to 79 create and interact Mojo primitives like **message pipes**, **data pipes**, and 80 **shared buffers**, as well as APIs to help bootstrap connections among 81 processes. 82 83 ## Platform Support API 84 Mojo provides a small collection of abstractions around platform-specific IPC 85 primitives to facilitate bootstrapping Mojo IPC between two processes. See the 86 [Platform API](/mojo/public/cpp/platform/README.md) documentation for details. 87 88 ## High-Level System APIs 89 There is a relatively small, higher-level system API for each supported 90 language, built upon the low-level C API. Like the C API, direct usage of these 91 system APIs is rare compared to the bindings APIs, but it is sometimes desirable 92 or necessary. 93 94 ### C++ 95 The [**C++ System API**](/mojo/public/cpp/system/README.md) provides a layer of 96 C++ helper classes and functions to make safe System API usage easier: 97 strongly-typed handle scopers, synchronous waiting operations, system handle 98 wrapping and unwrapping helpers, common handle operations, and utilities for 99 more easily watching handle state changes. 100 101 ### JavaScript 102 The [**JavaScript System API**](/third_party/blink/renderer/core/mojo/README.md) 103 exposes the Mojo primitives to JavaScript, covering all basic functionality of the 104 low-level C API. 105 106 ### Java 107 The [**Java System API**](/mojo/public/java/system/README.md) provides helper 108 classes for working with Mojo primitives, covering all basic functionality of 109 the low-level C API. 110 111 ## High-Level Bindings APIs 112 Typically developers do not use raw message pipe I/O directly, but instead 113 define some set of interfaces which are used to generate code that resembles 114 an idiomatic method-calling interface in the target language of choice. This is 115 the bindings layer. 116 117 ### Mojom IDL and Bindings Generator 118 Interfaces are defined using the 119 [**Mojom IDL**](/mojo/public/tools/bindings/README.md), which can be fed to the 120 [**bindings generator**](/mojo/public/tools/bindings/README.md) to generate code 121 in various supported languages. Generated code manages serialization and 122 deserialization of messages between interface clients and implementations, 123 simplifying the code -- and ultimately hiding the message pipe -- on either side 124 of an interface connection. 125 126 ### C++ Bindings 127 By far the most commonly used API defined by Mojo, the 128 [**C++ Bindings API**](/mojo/public/cpp/bindings/README.md) exposes a robust set 129 of features for interacting with message pipes via generated C++ bindings code, 130 including support for sets of related bindings endpoints, associated interfaces, 131 nested sync IPC, versioning, bad-message reporting, arbitrary message filter 132 injection, and convenient test facilities. 133 134 ### JavaScript Bindings 135 The [**JavaScript Bindings API**](/mojo/public/js/README.md) provides helper 136 classes for working with JavaScript code emitted by the bindings generator. 137 138 ### Java Bindings 139 The [**Java Bindings API**](/mojo/public/java/bindings/README.md) provides 140 helper classes for working with Java code emitted by the bindings generator. 141 142 ## FAQ 143 144 ### Why not protobuf? Why a new thing? 145 There are number of potentially decent answers to this question, but the 146 deal-breaker is that a useful IPC mechanism must support transfer of native 147 object handles (*e.g.* file descriptors) across process boundaries. Other 148 non-new IPC things that do support this capability (*e.g.* D-Bus) have their own 149 substantial deficiencies. 150 151 ### Are message pipes expensive? 152 No. As an implementation detail, creating a message pipe is essentially 153 generating two random numbers and stuffing them into a hash table, along with a 154 few tiny heap allocations. 155 156 ### So really, can I create like, thousands of them? 157 Yes! Nobody will mind. Create millions if you like. (OK but maybe don't.) 158 159 ### What are the performance characteristics of Mojo? 160 Compared to the old IPC in Chrome, making a Mojo call is about 1/3 faster and uses 161 1/3 fewer context switches. The full data is [available here](https://docs.google.com/document/d/1n7qYjQ5iy8xAkQVMYGqjIy_AXu2_JJtMoAcOOupO_jQ/edit). 162 163 ### Can I use in-process message pipes? 164 Yes, and message pipe usage is identical regardless of whether the pipe actually 165 crosses a process boundary -- in fact this detail is intentionally obscured. 166 167 Message pipes which don't cross a process boundary are efficient: sent messages 168 are never copied, and a write on one end will synchronously modify the message 169 queue on the other end. When working with generated C++ bindings, for example, 170 the net result is that an `InterfacePtr` on one thread sending a message to a 171 `Binding` on another thread (or even the same thread) is effectively a 172 `PostTask` to the `Binding`'s `TaskRunner` with the added -- but often small -- 173 costs of serialization, deserialization, validation, and some internal routing 174 logic. 175 176 ### What about ____? 177 178 Please post questions to 179 [`chromium-mojo (a] chromium.org`](https://groups.google.com/a/chromium.org/forum/#!forum/chromium-mojo)! 180 The list is quite responsive. 181 182